Ending immigration detention – a moral imperative

Posted: 24 September 2022

This article appeared in our magazine for Labour Party conference 2022

By Emma Jones, Oxford West & Abdingdon CLP

I won’t forget my first sight of Campsfield House Immigration Removal Centre.

I was there in the privileged position of observer, rather than detainee, but it was still a shock, particularly the height of the fences (20-foot-tall and topped with razor wire). More shocking to me was what the place represented. I was a student then, left-wing and sceptical of national pieties – but on seeing Campsfield I realised the extent of my naivety.

At some emotional level, I had regarded Britain as a place where certain things could not happen – indefinite detention without due process being one of them. Habeas Corpus and all that. The reality is horribly different: the UK is the only country in Europe that does not have a time limit on immigration detention and the net is cast wide.

As someone whose right to exist in this country has never been challenged, it was my privilege to be unaware of Campsfield’s existence until I became involved, in the early 2000s, in the fight to prevent the deportation of a fellow student to Afghanistan. If he had been detained, he would have found himself behind the wire and visiting him would have meant being searched before passing through five separate remote-controlled doors.

My friend was a former child refugee, whose extraordinary achievements might in other circumstances have been celebrated – as we do erratically decide to celebrate some refugees, and our own benevolence in welcoming them. Instead he was in mortal danger. The British state seemed hellbent on returning him to a war zone.

It was a situation so obviously and absurdly wrong as to be almost incomprehensible; another shock to realise that his case was in fact pretty routine. Bear in mind too that this was happening under a Labour government. (Des Browne was the immigration minister at the time; our petitions were addressed to him). In the end, my friend escaped detention and deportation but it was owing to a legal loophole and some wise advice – no thanks at all to New Labour.

Ahead of the twenty-fifth anniversary of Campsfield in 2018, Professor Danny Dorling wrote of “a legacy of shame. … Just as we remember workhouses, bedlams, and the most brutal of prisons from the past and wonder why they were introduced and why it took so long to dismantle them, so too will Campsfield House be remembered in future.” The closure of Campsfield was announced shortly afterwards but in June this year the Home Office announced plans for a new detention centre on the site.

The abuse that enables all other abuses

It is worth considering the history of immigration detention and detention centres if only to understand how powers once regarded as severe and exceptional and reserved for emergencies became widespread and accepted. Plenty of politicians would like us to believe that the current system is set in stone and that alternatives are unthinkable. In fact, the current system dates from the 1990s so those unable to imagine the alternative must be very young or have short memories.

Campsfield House opened in November 1993 and was greeted with protests. It is salutary to realise that ‘Britain jails refugees‘ is too obvious for a protest sign today. It’s a fact of life. ‘Stop Rwanda flights’, say our placards, but the Rwanda Plan (denounced as “immoral” by the Archbishop of Canterbury) will also become normal if the next Conservative Prime Minister gets their way. Normalcy is a dangerous drug; it kills the moral sense. Unless our protest succeeds, what now appears an Obvious Evil will become an Established Fact tacitly accepted by all future governments.

The detention estate is integral to the Hostile Environment in its current form. Or to put it another way, detention is the abuse that enables all the other abuses: from the Windrush Scandal to the Rwanda Plan. There are currently seven so-called “immigration removal centres” (IRCs) operational in the UK, along with several “residential short-term holding facilities” (RSTHFs), and a “pre-departure accommodation” (PDA) unit at Tinsley House where families with children are detained pending deportation. Other people are held under immigration powers in mainstream prisons. Recent years have also seen an expansion of quasi-detention, including the use of ex-army barracks and squalid hotels to hold asylum seekers for long periods in prison-like conditions.

Anyone deemed “subject to immigration control” is at risk of detention, from the newest arrivals to people who have lived in the UK for many years. Detention happens without warning and requires only the discretion of an immigration official, not a court or a judge. Despite Home Office claims to the contrary, survivors of torture, trafficking, rape and gender-based violence are routinely detained. Indeed, a recent report by Medical Justice, the charity that sends independent clinicians to all UK IRCs, concluded that Home Office safeguarding processes are “so ineffective they are basically fictional”.

Why do we let this happen?

Public consent for these myriad cruelties is obtained through a curious psychological trick: once people are imprisoned it becomes easier to think of them as dangerous or undeserving (or not to think of them at all). A government website calmly relates that 24,004 people entered immigration detention in the year ending June 2022. This is human rights abuse on a large scale. Behind the statistic are so many shattered lives, separated families, absent parents and traumatised children.

The vulnerability of detainees, the lack of access to justice (only around 50% of people in detention have legal representation), and the fact that so many of these places are run for profit by private security companies on the favoured national ethic of the race to bottom, means it is little wonder that the names of individual detention centres are synonymous with scandal and mistreatment, over and above the degrading fact of detention itself. The various reports and reviews make dismal reading (especially since they seem to make so little difference to policy makers) but they do at least prove that the British state knows exactly what it is doing.

Experts will tell you that the system is broken in about every conceivable respect – just ask Sir Stephen Shaw whose first review in 2016 determined that “detention in and of itself undermines welfare and contributes to vulnerability.” Is this really a revelation to anyone? Hunger strikes and incidents of self-harm occur every day in UK detention centres. “”

In the current climate, even the most dystopian imaginings are soon overtaken by reality. Russell T. Davies‘s eerily prophetic drama Years and Years (2019) showed disease running riot in filthy government-mandated detention facilities; by 2021, there was a mass Covid outbreak at the real-life Napier Barracks where “unlawfully housed” asylum seekers were lying “terrified in their beds”. (Napier Barracks is set to remain open until 2026.)

If nothing else, the last few years have shown the utter futility of attempting to outbid the Tories in performative cruelty. After threatened pushbacks and mass expulsions, what’s next? ‘Suicidal Afghan was ‘fine’ about being sent to Rwanda, Home Office officials claimed’, is only the latest in a series of headlines that should be impossible to forget, but will likely be displaced by the next horror.

What can we do?

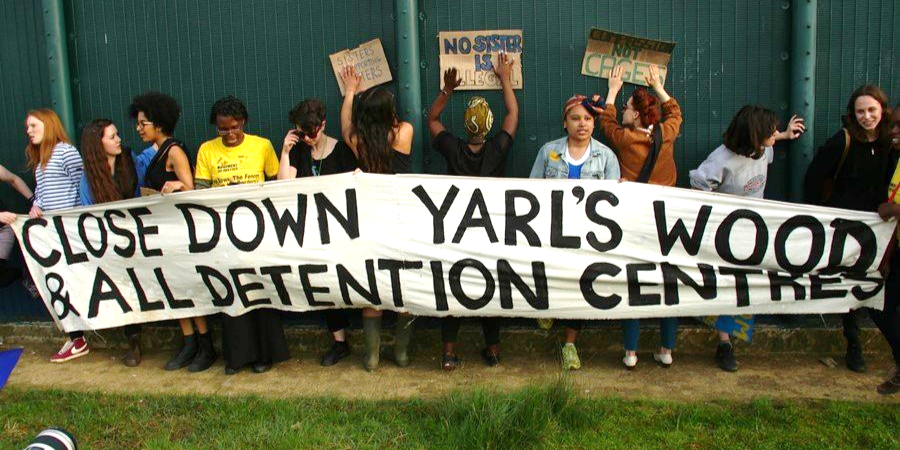

So what can be done? Political leadership is badly needed. In 2019, Labour Party Conference voted almost unanimously to close all detention centres as part of a wide-ranging motion to defend migrants’ rights. The 2019 manifesto fell short of members’ demands, though it did at least pledge to “end indefinite detention, review the alternatives to the inhumane conditions of detention centres, and close Yarl’s Wood and Brook House”, two particularly notorious facilities (both of which opened under New Labour).

We can and must go much further. The battle to end detention is being waged wherever detention centres exist and cries out for the active engagement of every single one of us. (Where is your nearest IRC? Look it up!) Groups like SOAS Detainee Support provide solidarity where it is most needed. Organising against the immigration raids that feed the machine is also vitally important, and can be hearteningly successful as a series of recent examples have shown.

Initiatives like These Walls Must Fall, the Solidarity Knows No Borders Network (organisers of the impressive Fair Immigration Movement (FIRM) Charter) and the new Action Against Detention & Deportations coalition, are the harbingers of change to come.

Above all, our migrant comrades at risk of detention and deportation must be defended with the full strength of our movement.

Our eyes are open and we cannot look away.