1905 and all that: How the labour movement debated Britain’s first immigration control

Posted: 13 August 2017

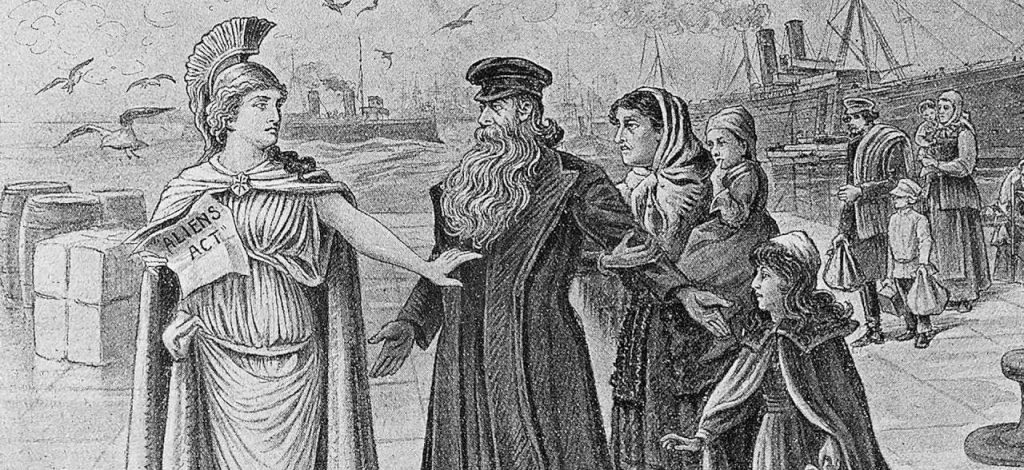

A 1906 cartoon protesting against barriers to refugees and migrants

By Daniel Randall

The debate now taking place within the labour movement in Britain over free movement has profound parallels with one which took place in the late 19th and early 20th centuries around the introduction of the “Aliens Act”, the first modern immigration control.

Prior to the Act’s introduction in 1905, Britain’s borders were effectively open. In the late 1800s, the country saw increasing levels of immigration of Jews from central and eastern Europe, fleeing both poverty and Tsarist persecution. Britain’s Jewish population more than trebled in the second half of the 19th century and early years of the 20th.

The arrival of poor Jews from the Tsarist Empire’s “Pale of Settlement” was met with a growing clamour, much of it explicitly antisemitic, for restrictions on immigration. In 1894, the Tory Lord Salisbury proposed an anti-immigration bill in the House of Lords. It was rejected by the Liberal government, but the Liberals were voted out the following year and the Tories took power. In 1903 they established a Royal Commission on Alien Immigration, which recommended that “persons […] likely to become a charge upon public funds” be refused entry into the country. Although all official policy proposals referred to “aliens”, it was clear that working-class Jews were the target.

The Trade Union Congress (TUC) had adopted a position in favour of controls in 1892. It had supported Salisbury’s bill, and in 1896 sent a delegation to the Home Secretary to petition in favour of it. Through 1892, 43 labour movement bodies had passed policies supporting immigration controls, including the powerful Trades Councils in Liverpool and Manchester.

The arguments are familiar: immigrant workers are prepared to work for lower wages than British workers, so their mere presence in the country puts downwards pressure on British workers’ wages. Then, as today, much of the debate was framed in terms of what immigrants contribute, with the 1905 bill denying entry to any “undesirable immigrant [who] cannot show that he has in his possession or is in a position to obtain the means of decently supporting himself”.

Migrant workers’ organisations fought back, supported by radicals and internationalists within the local labour movement. Many Jewish immigrants had brought strong working-class political traditions with them to Britain; indeed, accusations of the anarchist – and, later, Bolshevik – sedition Jews were bringing into the country was a key plank of anti-immigrant discourse. In 1895, 11 unions representing Jewish workers sponsored the publication of pamphlet, written by trade union activist Joseph Finn, entitled A Voice From The Aliens, which comprehensively refuted the case for immigration controls and appealed to English workers to see Jewish workers as their class brothers and sisters rather than their enemy.

The pamphlet argued: “It is, and always has been the policy of the ruling classes to attribute the sufferings and miseries of the masses (which are natural consequences of class rule and class exploitation) to all sorts of causes except the real ones.”

In 1902, the Federated Jewish Tailors’ Union held a conference to organise opposition to the TUC’s anti-immigration policy. 3,000 attended, with hundreds more spilling out onto the streets. Although many attendees were migrant workers, the conference was also addressed by opponents of immigration controls from the “local” labour movement. These included the Dockers’ Union’s Frank Brien, and Margaret Bondfield, the assistant secretary of the National Amalgamated Union of Shop Assistants, Warehousemen, and Clerks (an ancestor of Usdaw), who went on to become a minister in the 1929 Labour government, and the first woman to chair the TUC General Council.

Eleanor Marx was a leading voice of the labour movement’s pro-free movement radical left. She spoke at meetings to launch A Voice From The Aliens, and in 1902 helped found the “Aliens Defence League”, a migrant workers’ solidarity organisation committed to campaigning against immigration controls and for migrants’ rights.

History records that the pro-free movement wing of the labour movement lost; the 1905 Aliens Act was introduced, and Britain’s borders have remained restricted, to greater and lesser degrees, since. But the agitation of Jewish workers’ organisations and their allies helped change attitudes within the labour movement. In 1892, Manchester Trades Council had passed a resolution arguing: “It is time that workers of this country […] rose up and protested with firmness against the continuation of this curse [referring to mass immigration]”. By 1903, they had ceased campaigning for this policy. And in 1905, then TUC president James Sexton denounced the new immigration control at the TUC conference.

In 2017, the labour movement in Britain is again divided by similar questions. Some unions, like Unison and the Public and Commercial Services union (PCS), have passed policies in favour of free movement. Others have explicitly opposed it, such as my own union, the National Union of Rail, Maritime, and Transport workers (RMT).

The present debate contains several ironies: the GMB union passed anti-free movement policy at its 2017 congress, but also in 2017 established an “Eleanor Marx Prize” for the most inspirational woman member (Eleanor Marx helped found the GMB, and sat on its first executive committee). There is no need to wonder which side of the debate she would be on were she alive today.

The “Labour Leave” campaign, which promotes itself as Labour’s “official” pro-Brexit campaign group, circulated a foully anti-migrant screed denouncing migrant workers as “scab labour” (it later claimed it had done this in error). But far from being an anti-union, scab element within the working class in Britain, migrant workers have been at the forefront of some of the most significant recent victories, such as the reversals of outsourcing as the London School of Economics and SOAS.

The core of the debate has not changed since 1905. On one side, those that argue, often without evidence, that migrant labour undercuts domestic workers’ wages, terms, and conditions, and that the only solution is to reduce immigration. On the other, those who argue that the right to move freely between countries is a human right, and that only united struggle between local and migrant labour can push back exploitation.

The words of the resolution of the Federated Jewish Tailors’ Union conference are as true today as they were over a hundred years ago: “The vast amount of poverty and misery which exists is in no way due to the influx of foreign workmen but is the result of private ownership of the means of production”.

Note: Many of the statistics and references in this article are taken from Chapter 2 of That’s Funny, You Don’t Look Antisemitic, by Steve Cohen (1984), available online here.

Daniel Randall is a railway worker and workplace rep for the RMT union, Vice Chair of the RMT Bakerloo Line branch, and a co-host of the monthly labour movement podcast Labour Days.